When a crisis affects your company, you can do more than merely rely on contingency plans. Switch to “crisis innovation” and use scenarios as guidance, striking a balance between short-term and long-term survival. Crisis innovation follows a distinct set of rules, designed to navigate exceptional uncertainty and rapid change. Scenario analysis provides a kind of map of potential future threats and opportunities. As illustrated by our scenarios for The Pandemic Aftermath, they don’t need to be perfect to be valuable.

Published on September 4, 2023

Eric S. Yuan’s vision for a new video communications platform has made him a billionaire. When he founded Zoom in 2011, he couldn’t possibly have predicted that a global health crisis would one day push his platform from 10 million daily meeting participants to 300 million within just three months. When the opportunity arose, however, Yuan and his company were able to seize it and cope with the exploding demand as well as the many challenges that came with it.

Zoom is a unique, extreme example of a “crisis winner”. Yet, with a smart combination of scenario analysis and crisis innovation, almost any company has the chance of creating success stories – not despite, but because of the uncertainty during crisis. Scenarios serve as the „map“ detailing threats and opportunities, whereas crisis innovation equips businesses with the tools to navigate a promising path.

The following article showcases how companies can turn crisis and uncertainty into a source of innovation and competitive advantage in three chapters:

- Creating a map of future threats and opportunities with scenarios

- Activating crisis innovation mode

- Two tools for getting started

1. Creating a map of future threats and opportunities with scenarios

Long-term predictions of complex systems, such as markets, technology and societal developments, are notoriously inaccurate. Poor predictions were made about the time of peak oil, the future (in)significance of the internet, the outcome of Presidential elections, the course of the pandemic, and much more. This raises the question whether trying to create a meaningful map of future threats and opportunities is a futile endeavor. With the right scenario methodology, it isn’t. The following real-world scenario example illustrates how this can work in practice.

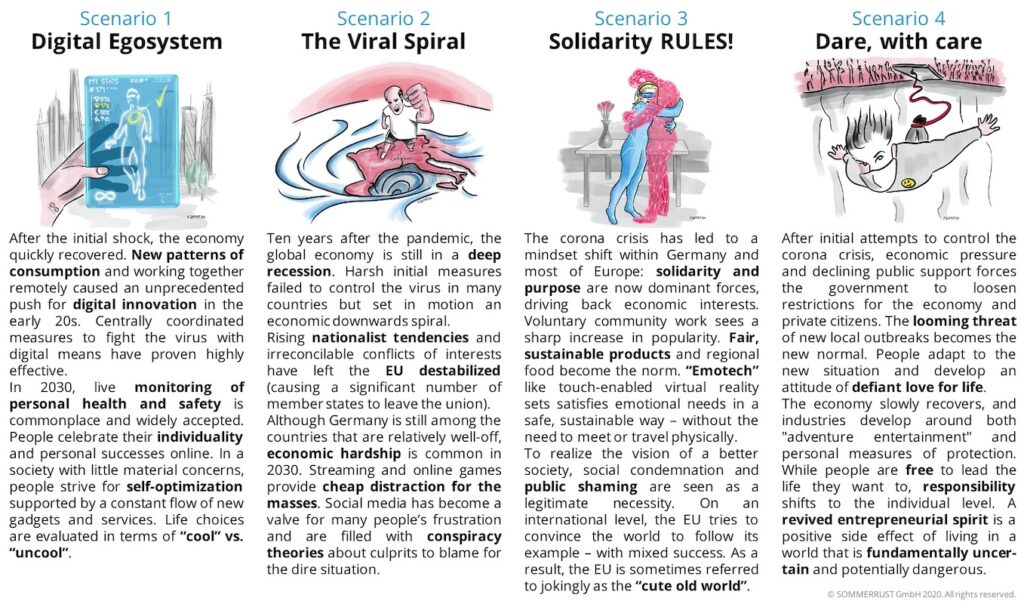

Example: “The Pandemic Aftermath” scenarios for Germany 2030

Three and a half years have passed since we created four scenarios about the pandemic aftermath in Germany. That timeframe corresponds to 34% of the 10-year scenario horizon — enough to look back again and reflect on how accurate the scenarios were knowing what we know today. Unlike for classical scenario planning approaches, the scenarios were created within just a few days using a Scenario Sprint. Despite the short process, we hoped to generate meaningful results that could inform better decisions. And indeed, the scenario process allowed us to anticipate a number of key developments at an very early stage of the crisis — including the availability of a vaccine in Germany in early 2021 (see this article for a review of results after one year). Meanwhile, our imagined emergence of “COVID-22” with a massive new wave of infections has also materialized in the form of the Omicron variant. Only the proposed timing in the so-called “Viral Spiral” scenario was a few months late. However, laying out plausible trajectories of the pandemic was merely a means to explore possible long-term consequences on our economy, our society – and even on the way we perceive the world around us. Comparing the scenario details with what we know today will give you a sense of the guidance that you can realistically expect [1].

And yet, reality taught us once more that scenarios are possibilities, not predictions.

The challenge of “Black Swan” events

As much as we got right, one important uncertainty we overlooked entirely: The invasion of Ukraine by Russian troops. This event could be considered a “black swan” — a devastating development that most people didn’t deem possible until it happened. It has had massive implications on the German economy like the initial shortage of gas supply and the surge of electricity prices.

Paradoxically, having scenarios could prove even more valuable for the things they did NOT anticipate, like the war in Ukraine. Although we didn’t consider the war as an explicit uncertainty, it resulted in some consequences that we did foresee within our scenarios — albeit for different reasons. Most notably, the war has (1) pushed the emotionalization as described in “Solidarity RULES!”, and (2) caused a serious disruption of international trade as part of “The Viral Spiral” scenario. Even as scenarios won’t eliminate uncertainty, even miss major possibilities, they can provide an invaluable reference for strategic decision-making and creating future-proof innovations.

Focus on doing the right things instead of being right

When being introduced to sound technology a century ago, Harry Warner of Warner Bros. apparently asked: “Who the hell wants to hear actors talk?”. Instead of dismissing the new technology in film altogether, however, he apparently added, “… The music — that’s the big plus about this!”. Warner Bros. did invest in sound technology and became a pioneer in their industry. What does this teach us? You may be wrong about the specifics initially (voice vs. music). What matters is to anticipate the larger change — that sound will be a thing — and to act on it.

Analogously, it is more important to prepare appropriately for a “Viral Spiral” scenario than getting all the details right that contribute to the underlying vicious cycle. When the effort of making the own supply chain more resilient is already underway, it will be much easier to deal with the specific supply chain challenges as they arise.

At the same time, it remains crucial to examine whether major developments shed a new light on the scenarios as a whole. For example, the war in Ukraine may dissolve the logical separation between “Solidarity RULES!” and “The Viral Spiral”: We initially believed that if things got really bad due to the pandemic, there would be limited space for solidarity within Germany and beyond. The aggression of Russia, however, could prove to become a uniting factor — a role that an anonymous virus cannot play to the same extent. When the map provided by your scenarios changes, new threats or opportunities may emerge.

2. Activating crisis innovation mode

When companies get hit hard by a crisis, they must keep their money together. Also, substantial management attention and resources may be required to reorganize and streamline the company. It seems natural to stop all non-vital innovation efforts until after the crisis. “Vital” means short-term survival in this case. However, such a course of action does not only ignore all the opportunities that specifically arise when things get shaken up in times of crisis, it may also jeopardize the long-term survival of the company.

We propose to balance short-term and long-term survival through “crisis innovation”. A simple set of prioritization rules may help to put it into practice:

No. 1: Fast go-to-market: cash will be scarce, so innovation projects that aim to commercialize existing company assets like a so-far unexploited technological development or data treasure are more favorable than R&D projects that start with square one. We call these project ideas “raw gems” as they can be turned into value-adding products relatively quickly without compromising on their chances of success.

No. 2: Push novel ideas: In times of crisis, uncertainty is even higher than usual. Assumptions that were once safe may no longer be. Once stable supply chains break. Demand changes. Markets get shaken up. This means that close-to-core innovations that are relatively sure bets in normal times may fail more often. Moreover, customers may be more willing to try something new — think of videoconferencing, online shopping, or a new hobby that works during a lockdown. In these cases, the chances of unconventional ideas succeeding may even increase. The time to go for something really new — maybe even radical — is during a crisis!

No. 3: Small is beautiful: Adjust your selection process to favor smaller projects. Kill or pause your big-ticket innovation projects to free resources if you have to (unless they are almost completed or directly benefit from the crisis). Approaches that use probability-adjusted returns to “calculate” the company’s ideal innovation portfolio may overestimate the predictability of innovation even in normal times. This problem gets worse when predictability drops further during times of crisis. Hedging your bets through more but smaller experiments now becomes much more attractive: The accuracy of probability estimates may suffer particularly for innovation efforts that run for a long time. These projects additionally face the problem that the underlying key assumptions must not only be valid in the beginning, but also to stay that way during the entire course of the project. Lockdowns, supply shortages, energy price shocks and rising interest rates are just a few examples of assumptions that will have ruined a considerable number of business cases during the last couple of years alone.

During crisis mode, many companies restrict innovation to projects that are directly approved by the board. Ironically, this procedure usually favors projects that are visible enough to get board-level attention (i.e., large projects), that seem clear and well understood (i.e., conventional ideas) or that sound very visionary to convey hope (i.e., with a distant go-to-market). Hence, “crisis innovation” in the sense described above may feel counterintuitive to many organizations.

It is all too easy to misinterpret the rules above when revenues plummet and the pressure grows. The following pitfalls stand out:

- “Go small” does not mean “kill all big ideas” — just stop the large projects that block a lot of resources. The long-term goal of a small project can be wildly ambitious while huge corporate transformations sometimes promise only incremental improvements. For example, a focused pilot application for Generative AI with one customer group may mark the beginning of a new era (cp. sound technology in film), compared to some company-wide IT transformation that eventually creates only moderate efficiency gains.

- The worst reaction, however, is to stop innovating altogether. Going back to innovation mode after the crisis may prove very difficult once the entrepreneurial minds have left and there is no strong, believable vision to go back to. It may feel wrong to spend money on innovation while employees get laid off at the same time. Yet, merely providing a fear-driven outlook of how to survive the storm will be much less engaging than linking it to a post-crisis vision that is worth fighting for.

This leads to the last two rules of crisis innovation:

No. 4: Try to be transparent and fair: When budgets get tight, having to say ‘no’ becomes more frequent. Explaining decisions therefore becomes even more important than during ordinary times. Treating people fairly will not be a trivial task. Mistakes will be made under pressure. Yet employees are usually quite good in distinguishing honest mistakes from dishonest ones, provided a certain level of trust still exists.

No. 5: Push responsibility for innovation downwards, not upwards: when it gets hectic, regular information flows and decision-making processes may break down or become too slow within the normal hierarchy (if they aren’t already). While the natural instinct during crisis may be to seize control of innovation projects and steer them more centrally, this will often only worsen the problem of wasting money though uncoordinated efforts. What projects may lack is clear goals and accountability, but rarely more “advice” from the top. Senior leadership can help by carving out an innovation budget for strategic topics, but how to use it should better be left to those close to the action.

3. Two tools for getting started

Critics may argue that many statements above were also true before the pandemic and the subsequent crises. This may be true, but a crisis tends to aggravate problems that already existed in innovation management before. The good news is that a crisis may also make it easier to correct some of these as routines get shaken up. It will still be difficult — the system will fight back. Two tools that we find useful to address this problem are “Lightning Scenarios” and “Pop-up Accelerators”:

1. Lightning Scenarios are combinations of important trends and the two most critical uncertainties. They help teams (re-)focus on the important things beyond the horizon rather than just on what’s urgent today. When constrained by time or budget, opting for a streamlined 4-hour Lightning Scenario workshop offers a practical starting point (see this website for more info). Moreover, with recent advancements in AI, Large Language Models such as GPT-4 can quickly generate rich and nuanced scenarios through smart prompt engineering. This enables teams to focus on discussing the implications of scenarios rather than spending time on their creation.

2. Pop-up Accelerators speed up innovation efforts without the commitment and lead time required to establish a full-scale accelerator organization. By leveraging teams of internal subject-matter experts, innovation professionals, and ideally some external expertise, the company can create effective, temporary “innovation bubbles”. A critical success factor is for senior management to protect these bubbles and their way of operating. This approach can also serve as an elegant way to introduce the five crisis innovation rules to the organization. If the pop-up accelerator proves valuable, it can become permanent at a later stage.

Conclusion

Some questions remain unanswered: Are we actually going to see a constant crisis mode in the coming years or will we get back to (a new) normal soon? What specific future do we need to prepare for with crisis innovation?

No set of scenarios can give definite answers to these questions. The “map” that scenarios provide will not be perfect. It will contain white spots (cp. the war in Ukraine). It will show some paths that don’t exist (scenario outcomes that do not materialize). And yet it is far better than having no map at all. Furthermore, crisis innovation as a way of operating will need to be adjusted to function with the established innovation culture of an organization. But if done well, scenarios and crisis innovation provide both the direction and the means to weather the storm and come out stronger than before the crisis.

Notes:

[1] We encourage the interested reader to consider the original scenarios from early 2020 as an example for what can be anticipated. However, beware of the so-called hindsight bias: although very little was actually known about the virus at the time, people tend to consider historic outcomes to be much more obvious than they were before they happened.

Source of cover image: Midjourney. This text has been edited with GPT-4.